“I keep my eyes always on the Lord. With him at my right hand, I will not be shaken. Therefore my heart is glad and my tongue rejoices; my body also will rest secure, because you will not abandon me to the realm of the dead, nor will you let your faithful one see decay. You make known to me the path of life; you will fill me with joy in your presence, with eternal pleasures at your right hand.” ~ Ps 16: 8-11

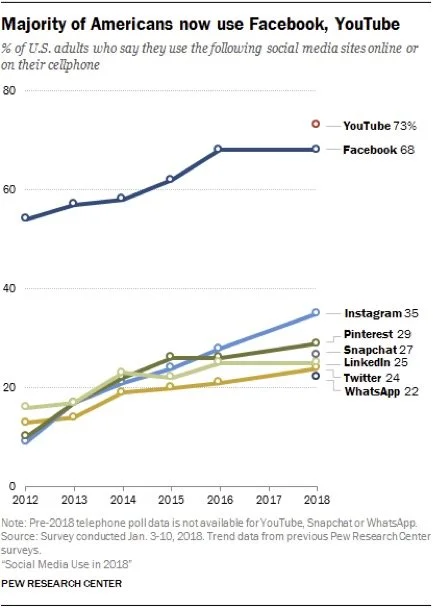

The question of salvation and damnation is an old one, tackled by many great religious thinkers living in and observing of the sinfulness of their age. The predicament is still alive and well in the Church today. A former student recently posted a video of Rev. Paul Washer on Facebook and asked his friends (including me) their take on the pastor’s fiery message. In this video, Washer proclaims,

There is only one thing that gave me a sleepless night. There is only one thing that troubled me all throughout the morning, and that is this: within a hundred years, a great majority of people in this building will possibly be in Hell. And many who even profess Jesus Christ as Lord will spend an eternity in Hell.”

Later on, he added,

In modern day evangelism, this precious doctrine [of regeneration] has been reduced to nothing more than a human decision to raise one’s hand, walk an aisle, or pray a “sinner’s prayer.” As a result, the majority of Americans believe that they’ve been “born again” (i.e., regenerated) even though their thoughts, words, and deeds are a continual contradiction to the nature and will of God.

I watched the video and honestly was stunned by his terse dialogue and seemingly cold, judgmental diagnosis of the human condition. It seemed so contrary to the image that I have perceived in the New Testament (and Old) that seems to show a God of great mercy and love, slow to anger, quick to forgive, a God who understands our need for a savior and joyfully, faithfully works with us through our weaknesses. Still, I recognize the perfection of God and the need for repentance of our sins. Holiness allows no corner for unrighteousness in Heaven.

Quite timely, I also recently read through Rob Bell’s Love Wins, and came across other proclamations from the other side of the salvation aisle, if you will, which also shocked me. Bell states,

A staggering number of people have been taught that a select few Christians will spend forever in a peaceful, joyous place called heaven while the rest of humanity spends forever in torment and punishment in hell with no chance for anything better. It’s been clearly communicated to many that this belief is a central truth of the Christian faith and to reject it is, in essence, to reject Jesus. This is misguided, toxic, and ultimately subverts the contagious spread of Jesus’ message of love, peace, forgiveness and joy that our world desperately needs to hear.

Later on, he concludes,

Millions have been taught that if they don’t believe, if they don’t accept in the right way according to the person telling them the gospel, and they were hit by a car and died later that same day, God would have no choice but to punish them forever in conscious torment in hell. God would, in essence, become a fundamentally different being to them in that moment of death, a different being to them forever. A loving heavenly father who will go to extraordinary lengths to have a relationship with them would, in the blink of an eye, become a cruel, mean, vicious tormenter who would insure that they would have no escape from an endless future of agony . . . If God can switch gears like that, switch entire modes of being that quickly, that raises a thousand questions about whether a being like this could ever be trusted. Let alone be good.

Bell’s take, though humanly sympathetic, appears to lack the depth of understanding when it comes to personal responsibility, and the reality of a sinless, holy God cohabitating eternally with his creations who have a carnality problem. Bell’s position might feel good, but so does heroin (I hear) before it destroys the body and ultimately one’s life. We are to ignore fashionable theologies that merely “say what [their] itching ears want to hear” (2 Tim 4:3).

So, I languished in conflict for a time—caught between two visions of God’s perspective on humanity, salvation, Heaven and Hell. Our society promotes one-sidedness, and condemns compromise. Either Washer was right, or Bell was—there cannot be any middle ground. Either God hates us in our wicked humanity or God loves us through our human weaknesses. It was quite nerve-wracking and I wished to avoid heresy (or hearsay).

Then, an unassuming story sincerely popped into mind, and it offered this view of human weakness and divine salvation for consideration:

Every person is like a small boat in a very big, angry ocean, and this boat has a serious, deadly leak. Without attention, the tiny boat will eventually sink into the murky, black depths of the ocean—all will be lost. Fortunately for each boat, a grand harbormaster is at their beckon call who has everything needed to rescue the most rotten of vessels. Moreover, the harbormaster has promised to haul each broken boat to a haven of safety no matter how much water is taken on or how low the boat goes into the water before sinking. Rescue is guaranteed immediately if any boat sends out a mayday for deliverance.

Of course, some boats assume that their leak problem is not that serious, and that they can be bailed out fast enough to keep up with the inflow of ocean water, but, of course, no one small boat has the ability or resources to bail continuously, daily, hourly, for 75-85 years (some ocean journeys take a lifetime). Sadly, these vain vessels eventually wait too long and their boats sink to the inky depths of Sheol, truly a tragedy considering how easily rescue might have come had they but called out for help. These boats’ vanity, their self-dependence, has cost them everything and rendered them dead in the water.

Being the best-equipped harbormaster in the world, he can and will eventually raise the boat, hoping to salvage whatever he can. These sunken boats, as with the others that come into harbor under happier circumstances, in time will face his scrutiny on what ultimately led them to their demise. His extensive nautical experience and understanding is beyond comparison or challenge. His judgment is fair and honest, and though he hopes for the best, he requires a truthful investigation of all the fateful factors. Justice will be dispensed—some boats will be decommissioned.

For those wise enough to call out for help, though, quicker than a flash the Harbormaster sends out his first mate, his very best worker, who has the tools and skills to quickly repair any leak, no matter what size, to keep the boat from fully submerging to its destruction. Of course, all boats are made from natural materials and thus other leaks are bound to appear over time (some boats have bigger leaks than others; some always leak in the stern—some in the bow, etc.), but still, the first mate expects this and is prepared to continue his work on the boat until his shift ends and the boat is saved.

The first mate never deserts his post because he deeply shares the heart and will of the Harbormaster, who doesn’t want any boats to founder. One lost boat is one boat too many on his watch, and he will not allow it as it up to him. Furthermore, he knows that without his assistance, all boats are ultimately doomed to destruction due to the deadly conditions of the deep and the (in)durability of the boat design. Still, any boat that calls out to the Harbormaster, who willingly receives assistance from the first mate, can be assured that the boat will make it home safe, someday, even in the roughest of seas or the most terrifying or enduring of storms.

Whether a boat is lost or saved depends solely on a honest realization of inadequacy, and a personal call for deliverance from the Harbormaster. No other rescue is possible from anyone or anything else.

Washer and Bell ultimately are both striving for the same thing despite their differences on the human and divine condition—they seek salvation and reconciliation for humanity. Washer is correct in that humanity is cut off from God because of our natural sin problem. Bell is correct in that God is not willing that any perish and so has provided a way to heal the relationship of humanity and God. Interestingly, both men call out for action in the lives of the believer.

Bell states, “If we want hell, if we want heaven, they are ours. That's how love works. It can't be forced, manipulated, or coerced. It always leaves room for the other to decide. God says yes, we can have what we want, because love wins.” Washer claims, "[Alot of people] think that Christianity is you doing all the righteous things you hate and avoiding all the wicked things you love in order to go to Heaven. No, that's a lost man with religion. A Christian is a person whose heart has been changed; they have new affections." Bell emphasizes the freedom that God gives us to choose our ultimate destiny. Washer emphasizes the consequences of those freedoms and how they can limit our relationship with God.

In their various ministries, these men have encouraged people to change their hearts and minds in order for people to repair their relationship with God and to reach out to each other in the love of Jesus. Though not perfect, it is clear that Washer and Bell both deeply care about God and humanity, but looking solely to them for “the Truth” will not accomplish much. For, in even grander fashion, God, the supreme Harbormaster, provides the rescue plan. He has listened intently throughout history for the urgent calls of all boats fearful of sinking into the abode of the dead, and most wonderfully, He faithfully reaches out to save and restore any who would allow Him on board their battered boat. Despite Washer and Bell’s stringent or lax or complex road to restoration, Romans 9 presents a simple plan of redemption to those who would heed its call.

But what does the Bible say? “The word is near you; it is in your mouth and in your heart,” that is, the message concerning faith that we proclaim: If you declare with your mouth, “Jesus is Lord,” and believe in your heart that God raised him from the dead, you will be saved. For it is with your heart that you believe and are justified, and it is with your mouth that you profess your faith and are saved.

Thus, when your boat is sinking, believe in the one who can, and lovingly will, pull you out of the dark depths into His wondrous light of salvation. God truly is the only avenue of our eternal rescue from the waters of damnation and ourselves.

(Copyright by John S. Knox, 2026)